How gut health shapes behaviour, anxiety, and learning

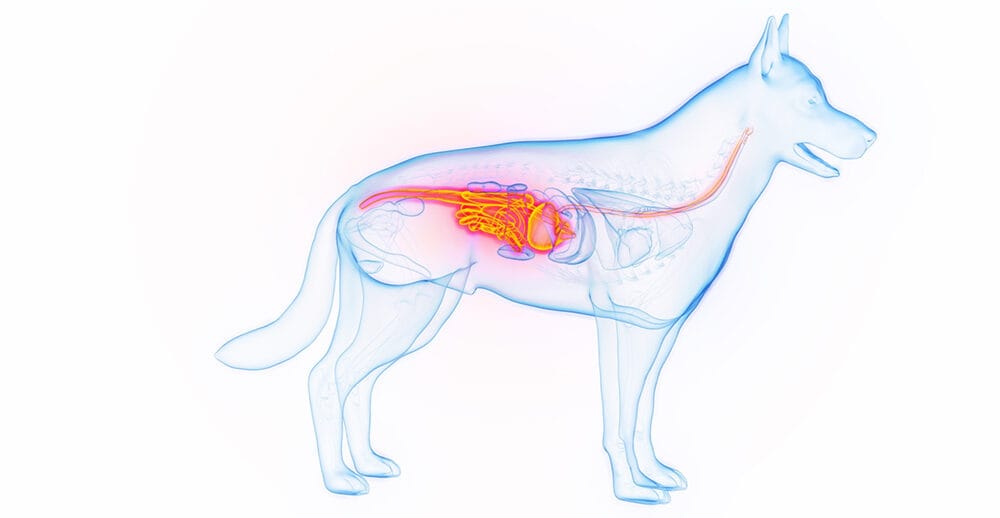

If you’ve lived with a dog who gets jumpy during storms, struggles with separation, or turns into a genius (or gremlin!) at training class, you’ve seen how tightly the body and mind intertwine. Over the last decade, science has shown that one surprising meeting point is the gut–brain axis (GBA): a two-way communication network linking the gastrointestinal tract to the central nervous system via nerves (notably the vagus nerve), immune pathways, hormones, and microbial metabolites. In humans and laboratory animals, the microbiome can influence mood, stress responses, and cognition. In dogs, the picture is newer, but it’s getting clearer.

Below, we translate the latest findings into everyday decisions you can make at the food bowl (and beyond) to help anxious dogs cope better, support learning, and keep behaviour on an even keel.

What the science says (so far)

1) The canine microbiome is linked to behaviour

A 2025 study in Scientific Reports used machine-learning models to predict behavioural group (e.g., anxiety, aggression) from dogs’ gut microbiota. While overall differences were subtle, certain bacterial signatures – especially Blautia – were consistently associated with anxiety profiles. This doesn’t prove cause and effect, but it strengthens the link between microbiome composition and behaviour in pet dogs.

In parallel, reviews summarising canine and translational data argue that microbial activity can modulate stress circuits, suggesting therapeutic potential for ‘psychobiotic’ strategies in dogs – though the field is young and needs more controlled trials.

2) Stress can reshape the gut

Short, acute stressors that are common in pet life (travel, novel environments, social stress) can shift gut communities and digestive health in dogs. This aligns with human and rodent work showing bidirectional stress-microbiome effects and helps explain why anxious periods sometimes coincide with tummy troubles, or vice versa.

3) Microbes and cognition

Emerging work has linked specific microbes (for example, Bifidobacterium pseudolongum) with better memory performance in puppies, hinting that gut residents could influence learning windows. We’re only at an early stage in the research process, but the findings do dovetail with broader evidence that microbial metabolites (like short-chain fatty acids) can affect neuroplasticity and inflammation, two pillars of learning.

4) Changing the microbiome can change behaviour

In a 2024 pilot study in a canine model of drug-resistant epilepsy, faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) not only modulated seizures but reduced anxiety/ADHD-like symptoms. This provided a striking, if small-sample, demonstration that targeted microbiome interventions can affect brain-behaviour outcomes. Academic and lay summaries echoed the finding, with appropriate caution about scale and replication.

FMT in dogs stands for Faecal Microbiota Transplantation, a procedure where faecal matter from a healthy donor is transferred to a sick dog to restore a healthy gut microbiome. This treatment aims to address imbalances in the dog’s gut bacteria, which can be caused by various factors like disease, infection, or prolonged antibiotic use.

How the gut ‘talks’ to the brain

- Neural routes: Microbial metabolites (e.g., butyrate) and gut hormones can stimulate the vagus nerve, influencing brain regions involved in stress and mood.

- Immune routes: Dysbiosis (an imbalanced microbiome) can increase gut permeability and cause low-grade inflammation, which in turn can alter behaviour and cognition.

- Endocrine routes: Microbes affect stress-axis signalling (HPA axis), tuning how dogs respond to fear or novelty.

Practical feeding strategies to support behaviour, anxiety and learning

The goal isn’t to chase a single ‘magic’ supplement. It’s to build a resilient, diverse microbiome with everyday choices and then layer targeted tools (pre/pro/post-biotics) when they make sense for your dog.

1) Start with the foundation: complete, balanced nutrition and weight control

A well-formulated diet provides the amino acids, essential fats, vitamins, and minerals needed for neurotransmitters, myelin, and immune regulation, all elements influencing behaviour. Keep body condition lean: excess fat tissue (adiposity) raises inflammatory tone, which can worsen anxiety and impair learning. Reviews in dogs and cats consistently connect microbiome stability with appropriate, balanced feeding.

How to apply:

- Feed a complete diet from a reputable brand or a qualified nutritionist-formulated home-prepared plan.

- Monitor body condition score monthly and adjust portions early in response to changes.

2) Feed the microbiome with prebiotic fibres

Prebiotics (non-digestible fibres such as FOS, MOS, inulin, and certain resistant starches) selectively feed beneficial microbes, encouraging production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) that support gut barrier integrity and may calm neuro-inflammation. In dogs, prebiotics improve stool quality and can stabilise communities disrupted by stress or diet shifts.

How to apply:

- Look for complete diets or supplements listing FOS/inulin/MOS.

- Introduce slowly over seven to ten days to avoid gas/loose stools.

3) Consider probiotics, but think strain, dose, and purpose

Probiotic effects are strain-specific. Reviews cataloguing canine-derived strains show benefits for gut health; early evidence (largely translational) suggests some strains may reduce anxiety-like behaviours via immune and vagal pathways. Veterinary institutions now discuss mental-health benefits as a promising frontier.

How to apply:

- Choose products with named strains (e.g., Lactobacillus rhamnosus, Bifidobacterium longum) and Colony Forming Unit (CFU) counts at end of shelf-life.

- Use for four to eight weeks before judging the impact. It is advised to keep a simple behaviour log (restlessness, reactivity, settle time) during this time.

- Chat to your vet before adding probiotics if your dog is immunocompromised or on medication.

4) Don’t forget postbiotics and fermented foods (with care)

Postbiotics (beneficial microbial metabolites) are gaining traction in pet nutrition. While canine-specific behavioural data are sparse, postbiotic-enriched diets may deliver short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and microbial cell components that modulate immune tone. Fermented additions (plain kefir/yoghurt) can be helpful for some dogs, but lactose sensitivity and added sugars need to be avoided so ask your vet before you experiment.

5) Use elimination and simplification strategically

For dogs with chronic gastrointestinal upsets and behaviour changes, a limited-ingredient or hydrolysed diet trial can reduce immune ‘noise’ from food reactions, sometimes improving restfulness and trainability. While this is clinical common sense rather than gut-brain-axis-specific proof, it fits the principle: reduce gut inflammation to help the brain.

6) When to think about FMT

Given early data in epileptic dogs with behavioural comorbidities, FMT is an intriguing vet-led option in highly selected cases (e.g., refractory GI disease with behavioural overlay, or specific neurological comorbidities). It remains experimental in general practice with protocols, donor screening, and long-term outcomes still needing standardisation. For more information, we advise you chat to your vet or specialist centre.

Beyond the bowl: lifestyle steps that help the gut and the mind

1) Train the stress system

Because acute stress can nudge the microbiome off balance, predictable routines, choice-based handling, and gradual desensitisation (to alone-time, travel, visitors, storms) do double duty: they reduce behavioural flare-ups and protect gut stability.

Try:

- Daily ‘decompression’ sniff-walks

- Five to ten minutes of easy trick training for positive prediction error (dog learns ‘I can cope and win’)

- A quiet, scent-enriched rest space (lick mats, stuffed toys, chew items)

2) Move the body, feed the brain

Exercise modulates the microbiome and supports neuroplasticity. Gentle aerobic work (brisk walks, controlled play, swimming) plus short shaping sessions can improve sleep quality and stress resilience, both crucial for anxious dogs and for learners. It is worth noting that exercise-microbiome interactions in dogs continue to be explored with broader longevity work suggesting parallel benefits.

3) Dental and GI health are part of behavioural health

Oral pain and chronic gut irritation elevate inflammatory mediators and stress hormones. Routine dental care and timely treatment of GI disease indirectly support calmer behaviour and better focus. This point is being increasingly emphasised in veterinary communications on the gut-brain-axis connection.

Putting it together: a four-week starter plan

Week 1: Stabilise and log

- Keep current complete diet; add a behaviour and stool diary (rate: anxiety 0–5, settle time, stool consistency).

- Introduce a predictable daily rhythm (feeding, walks, decompression).

- Begin five minutes/day of low-frustration training (hand-target, mat settle).

Week 2: Feed the microbiome

- Add a prebiotic fibre (FOS/inulin) at a low dose and increase gradually.

- Introduce a named-strain probiotic product for approximately six to eight weeks.

Week 3: Enrichment and exercise

- Rotate sniff and seek games; add one new texture/surface walk for confidence.

- Two extra short aerobic sessions per week (age-appropriate).

Week 4: Review and decide

- Compare the diary to the baseline.

- If anxiety remains high (e.g., separation, sound phobia), loop in your vet/behaviourist; consider a diet trial or medical work-up.

- For complex cases with GI and behaviour issues, discuss the suitability of advanced options (e.g., hydrolysed diets, referral; in rare cases, FMT research pathways).

Ask DQ

Q: Which probiotic is best for anxiety?

A: There isn’t a universal winner. Effects are strain-specific, product quality varies, and many canine studies are small. Start with reputable, strain-named products, give them time (four to eight weeks), and monitor behaviour and then adjust with your vet’s guidance.

Q: Can I fix behaviour with diet alone?

A: Diet can lower the ‘noise floor’ by reducing gut-driven inflammation or discomfort, making behaviour therapy work better, but most anxiety issues still need behaviour modification and, in some cases, medication prescribed by your vet.

Q: Is FMT a cure?

A: No. It’s promising in specific research contexts (e.g., epilepsy with behavioural comorbidities) but not a mainstream cure-all. Proceed only under veterinary supervision.

Key takeaways

- The gut and brain are in constant conversation in dogs. Microbiome shifts correlate with anxiety and aggression, and targeted changes can influence behaviour in some settings.

- Build from fundamentals: balanced diet, healthy weight, prebiotic fibre, and consistent routines. Layer strain-specific probiotics judiciously and give them time.

- Manage stress proactively, because stress can jolt the gut, and a calmer gut can help produce a calmer mind.

- Advanced tools like FMT are exciting but remain specialist, research-led options.