SOUTH AFRICA'S PREMIER DOG MAGAZINE

DIGITAL ISSUE 14B | 2025

Hello and welcome to another edition of DQ Magazine!

Every month, we bring you stories that celebrate the incredible bond between people and dogs, but also challenge us to think a little deeper about how we care for them.

This month we explore the questions and insights shaping modern dog ownership – from the science behind behaviour and health to the daily choices that affect our dogs’ wellbeing. Our aim is to share clear, research-based perspectives that help you understand your dog more deeply and support them to thrive.

At DQ, we know our readers are already passionate and knowledgeable. Our role is to dig into the detail, highlight the latest thinking, and celebrate the joy and complexity of living with dogs. We hope you find plenty to reflect on, and practical ideas you can put into action.

Until next time!

Lizzie and

the DQ team xxx

Dr Lizzie Harrison | Editor

Designer | Mauray Wolff

DIGITAL ISSUE 14B | 2025

CONTENTS

Dogs as ‘personal brands’

Why our companions are more than status symbols

Breed-linked health risks

An honest look at inherited conditions and how owners can advocate for their dogs

Canine cancer awareness

Most common cancers in dogs, early warning signs, and new treatment options

The canine athlete’s brain

How stress, routine, and training impact cognition and performance

The rise of tick-borne diseases

What’s happening in South Africa

It’s quality that counts

Why protein quality matters more than protein quantity in dog diets

The shy dog revolution

Celebrating introverted personalities rather than trying to ‘fix’ them

Fostering puppies

Georgia’s journey with Woodrock Animal Shelter

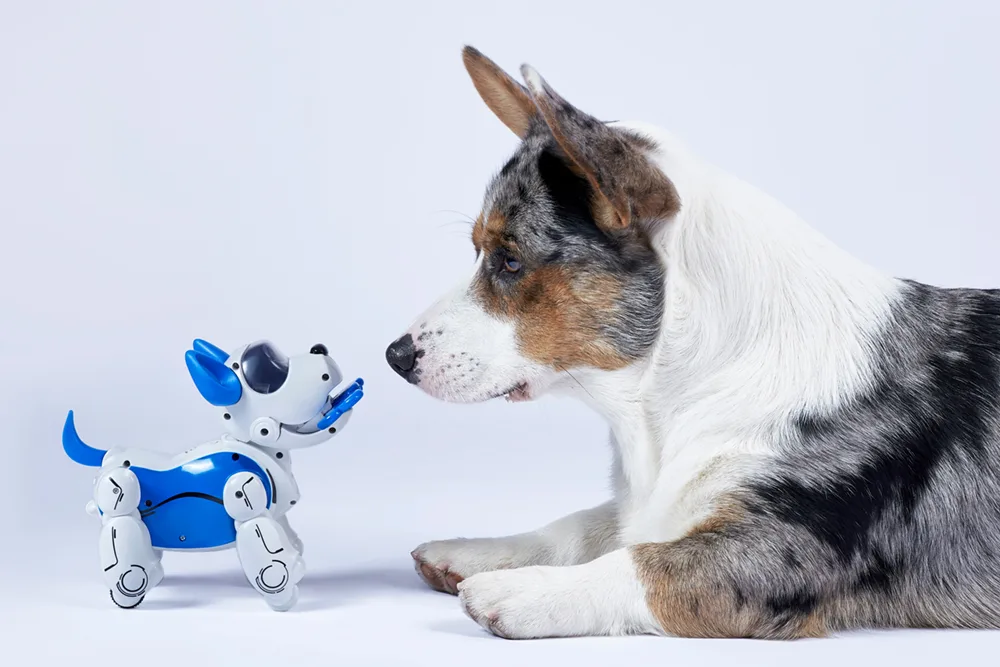

The new wave of tech for dogs

GPS trackers, activity monitors, AI feeders: gimmick or game-changer?

Ask DQ

Your questions answered

Products we love

Shopping

DOGS AS

‘PERSONAL BRANDS’

Why our companions are more than status symbols

Social media is full of trends – some fun, some thought-provoking, and some that leave us cringing a little. A recent one making the rounds is the idea that the breed of dog you own is part of your personal brand. In this way of thinking, a Poodle or a Pomeranian isn’t just a pet, it’s a reflection of your taste, your image, or even your home décor.

It’s not hard to see where this idea comes from. For a long time, brands have been part of identity: the car you drive, the clothes you wear, the coffee you order. In a world where Instagram feeds are curated like magazines, some people extend this thinking to their dogs – positioning them as a kind of ‘status symbol’ or an accessory to a particular lifestyle. A hypoallergenic breed, for example, is presented as perfect for the household where expensive furniture must never be covered in dog hair.

But while the concept might be catchy, it’s also troubling. Dogs are not commodities; they’re companions. Framing them as part of a personal brand risks turning living, feeling beings into aesthetic choices.

UNDERSTANDING THE CONCEPT

In marketing terms, a personal brand is the image and reputation you project into the world, and is often consciously curated through social media. The dog-as-brand idea slots neatly into this logic: different breeds signal different qualities.

French Bulldogs

may be seen as trendy, urban, and social media-friendly.

Poodles

could be framed as elegant, allergy-friendly, and tidy.

Border Collies

might project an outdoorsy, active lifestyle.

When reduced to this, dogs become props to underline a persona, rather than family members with needs, quirks, and value of their own.

WHY IT'S PROBLEMATIC

There are three main reasons this trend is worth challenging:

- It promotes shallow choices. People might pick a breed based on image rather than suitability, ignoring energy levels, health issues, or temperament. A breed that looks chic on Instagram may be completely unsuitable for their lifestyle.

- It diminishes welfare. Seeing dogs as accessories makes it easier to overlook their needs. A Border Collie isn’t an ‘active brand choice’ - it’s a working breed that can suffer if not given enough exercise and stimulation. Buying yourself the latest trainers from a sports brand and then never hitting the gym doesn’t affect the shoes, but doing the same to a dog is a welfare issue.

- It risks disposability. If a dog no longer ‘fits the brand,’ or if trends shift, the animal can be neglected or rehomed. We already see this with sudden surges (and abandonments) of breeds that go viral online.

WHAT REALLY MATTERS

Yes, our dogs do say something about us, but not in the way an Instagram reel might suggest. They show that we are willing to care, commit, and share our lives with another species. They reveal patience, empathy, humour, and resilience. They show that we are guardians, not consumers.

Choosing a dog should never be about curating a ‘look.’ It should be about:

• Temperament: Does this dog’s nature suit your family and lifestyle?

• Welfare: Can you meet this breed’s exercise, training, and health needs?

• Commitment: Are you prepared for 10–15 years of care, through every stage of life?

FINAL THOUGHTS

Dogs enrich our lives in countless ways, but they are not props in a personal brand. They’re living, breathing companions with needs, personalities, and value far beyond aesthetics. In a world obsessed with image, it’s worth remembering this.

BREED-LINKED

HEALTH RISKS

An honest look at inherited conditions

and how owners can advocate for their dogs

When we choose a dog, we often focus on their looks, temperament, and how well they’ll fit into our family life. But beneath the surface, each breed carries its own set of inherited health risks. Some are mild and easily managed; others can seriously affect a dog’s quality of life. Understanding these risks doesn’t make us love our chosen breed any less, or necessarily reject that breed going forward; it just makes us better guardians, better advocates, and more responsible owners.

THE HIDDEN PRICE OF SELECTIVE BREEDING

Dogs have been bred for centuries with specific purposes in mind: guarding, herding, companionship, hunting, or simply aesthetics. This selective breeding has given us the incredible diversity we see today, but it has also concentrated certain genetic weaknesses.

For example:

- Brachycephalic breeds (Pugs, Bulldogs, French Bulldogs) are prone to brachycephalic airway syndrome, a condition that makes breathing difficult and can affect exercise tolerance and even sleep.

- Large breeds such as German Shepherds, Labradors, and Rottweilers face higher risks of hip and elbow dysplasia, painful conditions that can lead to arthritis.

- Cavalier King Charles Spaniels often suffer from mitral valve disease, a serious heart problem that can shorten their life spans.

- Dachshunds and other long-backed breeds are predisposed to intervertebral disc disease, which can cause paralysis if untreated.

- Shar Peis are prone to entropion (inward-rolling eyelids), causing discomfort and repeated surgeries.

These are just a handful of examples, and ultimately, every breed has its vulnerabilities.

Hybrid vigour vs. purebreds

It’s often said that mixed-breed dogs are automatically healthier. While they may benefit from a wider genetic pool (reducing the risk of two faulty genes pairing up), they are not immune to disease. Hip dysplasia, for instance, is found in both purebreds and mixed breeds. The key lies not in whether a dog is purebred or mixed, but in whether breeders use health testing and responsible pairings.

DID YOU KNOW?

Many pedigree breeds have closed studbooks, meaning no new genetic material can be introduced. Over generations, this leads to inbreeding, smaller gene pools, and an increased risk of inherited disease. For example, a 2015 study in the Canine Genetics and Epidemiology journal showed that several popular breeds in the UK had effective population sizes far too small to maintain genetic diversity long-term.

The South African context

South Africa faces unique challenges. While many breeders here are passionate and responsible, health testing is not yet uniformly applied across breeds. Importing dogs from overseas can bring both genetic advantages and risks, depending on the lines chosen. Added to this is limited access to some of the advanced screening schemes (like the UK’s BVA/KC hip scoring or the Swedish elbow index), which means owners must rely heavily on transparency and trust.

Veterinary specialists in Johannesburg and Cape Town report that orthopaedic issues, brachycephalic airway cases, and inherited eye diseases are among the most frequent breed-linked conditions they see. Awareness is growing, but more still needs to be done.

WHY HONESTY MATTERS

There’s a tendency, especially among breeders and breed enthusiasts, to downplay these risks for fear of deterring potential buyers. However, the truth is that transparency helps dogs. When owners are aware of what to look out for, they can seek early treatment, adjust management, and advocate for healthier breeding practices.

By talking openly about breed-linked conditions, we encourage responsible breeding, informed ownership, and, ultimately, healthier dogs.

PREVALENCE SNAPSHOT

- Up to 70% of bulldogs show clinical signs of airway obstruction before their first birthday (Cambridge BOAS Research Group, 2021).

- Mitral valve disease affects over 90% of Cavalier King Charles spaniels by age 10 (British Veterinary Association, 2018).

- In South Africa, hip dysplasia is reported as one of the most common inherited conditions seen in large-breed dogs by local orthopaedic specialists

HOW OWNERS CAN ADVOCATE FOR THEIR DOGS

1. Ask the right questions before you buy or adopt

- Has the breeder carried out health testing for known conditions in the breed?

- What’s the average lifespan in their lines?

- Are they breeding for function and welfare, not just appearance?

2. Support ethical breeders

Good breeders prioritise health over exaggerated looks. They screen for inherited conditions and are honest about potential risks. Supporting them means rewarding responsible practices.

3. Get to know your breed’s red flags

Make sure you know the health conditions your particular breed of dog is susceptible to so you can recognise the early signs. For example, recognising subtle breathing difficulty in a Bulldog or early stiffness in a Labrador could make all the difference to their long term quality of life.

4. Work with your vet

Regular check-ups allow vets to spot issues early. Share your concerns, ask about breed risks, and consider screening tests when appropriate.

5. Speak up

Breed clubs, kennel clubs, and even lawmakers respond to public pressure. Advocate for changes to breed standards that prioritise health and function. The more voices raised for healthier dogs, the harder it is to ignore them.

THE FUTURE

The good news is that change is possible. More breeders are embracing DNA testing, more owners are demanding transparency, and welfare organisations are calling for reform.

As guardians, we can help accelerate this change by asking tough questions, making responsible choices, and always prioritising dogs’ welfare above fashion and looks.

DID YOU KNOW?

Encouragingly, some countries are beginning to change. The Dutch Kennel Club has introduced restrictions on breeding extremely short-nosed brachycephalic dogs, and in Scandinavia, certain exaggerated conformations are no longer acceptable in the show ring. These changes reflect growing recognition that beauty should never come before welfare.

FINAL THOUGHTS

Loving a breed means loving it enough to want better for it. By acknowledging the health challenges associated with certain breeds and advocating for change, we can ensure that the dogs we adore today will live longer, happier, and healthier lives tomorrow.

CANINE

CANCER

AWARENESS

Most common cancers in dogs,

early warning signs,

and new treatment options

Cancer is one of the leading causes of death in dogs worldwide. Just like in humans, it can appear in many forms, affect dogs of any age, and vary from treatable to life-threatening. For owners, the thought of cancer is frightening, but awareness is very powerful. Knowing the risks, recognising early signs, and understanding treatment options can help you advocate for your dog and improve their chances of living a longer, healthier life.

MOST COMMON CANCERS IN DOGS

Certain cancers occur more frequently in dogs, and some breeds are more at risk due to genetics. The most commonly diagnosed include:

- Lymphoma: A cancer of the lymphatic system, often first noticed as swollen lymph nodes under the jaw or behind the knees.

- Mast cell tumours: Skin cancers that can look like harmless lumps but may behave aggressively.

- Osteosarcoma: A painful bone cancer, particularly common in large and giant breeds such as Rottweilers and Great Danes.

- Hemangiosarcoma: A cancer of blood vessel walls, often affecting the spleen or heart, notorious for being silent until advanced.

- Mammary gland tumours: Especially common in unspayed females; early spaying significantly reduces risk.

- Melanoma: Often found in the mouth or on the skin, sometimes highly malignant.

MYTH – BUSTING

MYTH: Cancer always means a poor quality of life.

BUSTED: Many dogs live happily for months or years with treatment.

EARLY WARNING SIGNS

One of the greatest challenges is that cancer can look like many other, less serious conditions. Owners should always investigate:

- new lumps or bumps, or changes in existing ones

- unexplained weight loss or loss of appetite

- persistent lameness or swelling of a limb

- lethargy, weakness, or collapse

- wounds or sores that don’t heal

- changes in the mouth, such as pigmented patches, bleeding, or bad odour

- bloated abdomen

- sudden weakness

While not every lump is cancer, the safest approach is ‘check early, treat early.’ A fine needle aspirate or biopsy performed by your vet is often quick, minimally invasive, and provides vital information.

DID YOU KNOW?

Emerging research is also exploring liquid biopsies (blood tests that can detect tumour DNA early), which may one day allow for routine cancer screening in at-risk breeds.

RISK FACTORS AND PREVENTION

While cancer often seems to strike at random, several factors can increase the likelihood of a diagnosis:

- Age - most cancers are diagnosed in middle-aged and senior dogs.

- Breed - certain breeds have higher incidences due to inherited genetic risks (see sidebar).

- Sex and hormones - unspayed females are at much higher risk of mammary cancer.

- Lifestyle and environment - obesity, exposure to tobacco smoke, and sun exposure in pale or short-haired dogs all play a role.

While there’s no way to eliminate risk completely, owners can help by:

- keeping dogs lean and fit,

- avoiding exposure to second-hand smoke,

- providing sun protection for pale-skinned breeds, and

- scheduling regular veterinary check-ups.

Breeds at higher risk

- Golden Retrievers – lymphoma, hemangiosarcoma

- Boxers – mast cell tumours, brain tumours

- Bernese Mountain Dogs – osteosarcoma, histiocytic sarcoma

- Rottweilers – osteosarcoma

- Scottish Terriers – bladder cancer

- Flat-coated Retrievers – malignant histiocytosis.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Veterinary oncology has advanced rapidly in recent years. Depending on the type and stage of cancer, treatments may include:

- Surgery – Removing tumours is often the first line of defence, especially for skin or mammary cancers.

- Chemotherapy – Usually given at lower, gentler doses than in human medicine, meaning most dogs tolerate it with minimal side effects.

- Radiation therapy – Available in some specialised centres, used for localised cancers such as nasal tumours.

- Immunotherapy – A growing field that uses vaccines or immune-targeting drugs to help the dog’s own system fight cancer.

- Targeted therapies – newer drugs such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors are being used for mast cell tumours and other cancers.

- Palliative care – Pain management, dietary support, and lifestyle adjustments to maintain quality of life.

MYTH – BUSTING

MYTH: Chemotherapy is cruel.

BUSTED: Most dogs tolerate it well, with far fewer side effects than humans.

A SOUTH AFRICAN PERSPECTIVE

While South Africa does not yet have as many veterinary oncology centres as Europe or the USA, there are specialist vets and referral hospitals offering advanced cancer care, including chemotherapy and complex surgeries like amputations for osteosarcoma. Insurance cover is increasingly relevant, as treatments can be costly. Awareness among owners is also growing, with more people choosing to investigate new health problems rather than dismissing them.

ADVOCATING FOR YOUR DOG

- Do regular checks – run your hands over your dog once a week to feel for new lumps.

- Spay/neuter responsibly – early spaying dramatically reduces mammary cancer risk.

- Don’t delay vet visits – early detection improves outcomes.

- Ask about options – if your vet diagnoses cancer, request a referral to a specialist for the full range of treatments.

MYTH – BUSTING

MYTH: It’s not worth treating older dogs.

BUSTED: Age is less important than overall health and quality of life.

FINAL THOUGHTS

Hearing the word ‘cancer’ in the vet’s office is often our worst nightmare as owners, but it is not always a death sentence. With earlier diagnosis, better treatments, and owners who advocate strongly for their companions, many dogs live longer, happier lives than ever before.

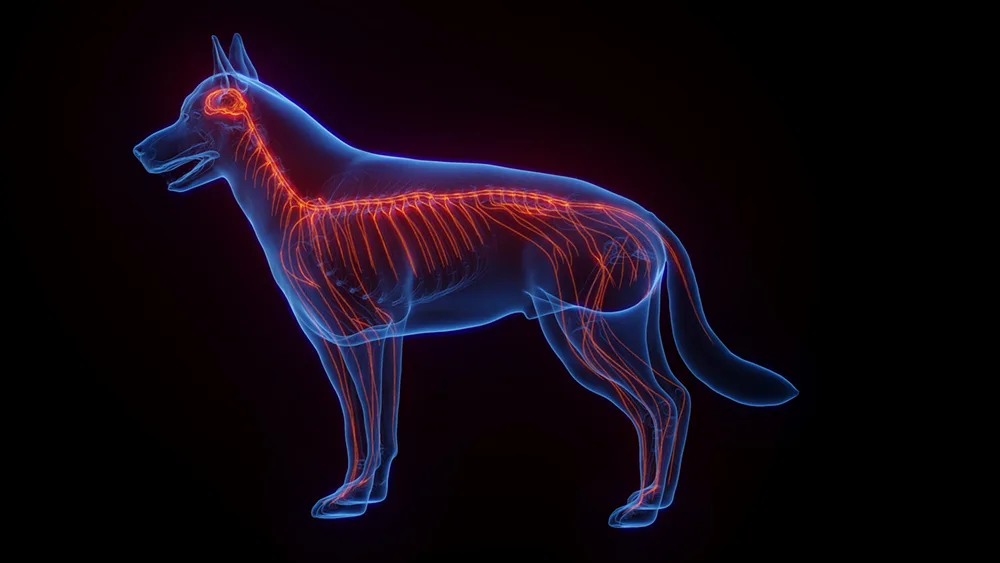

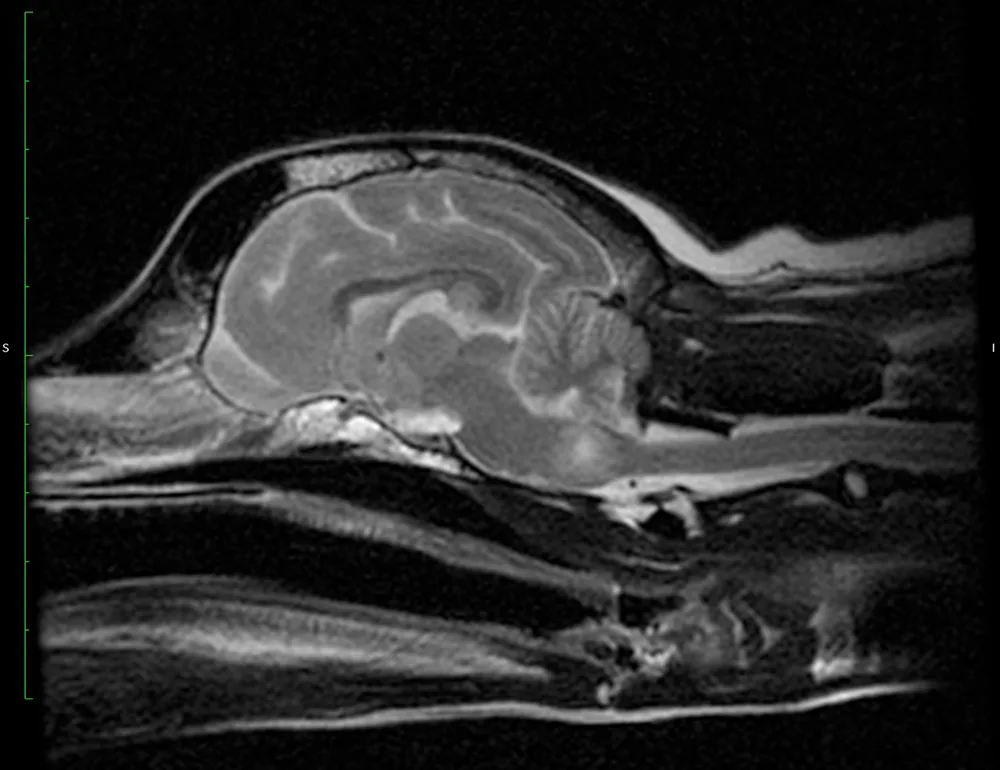

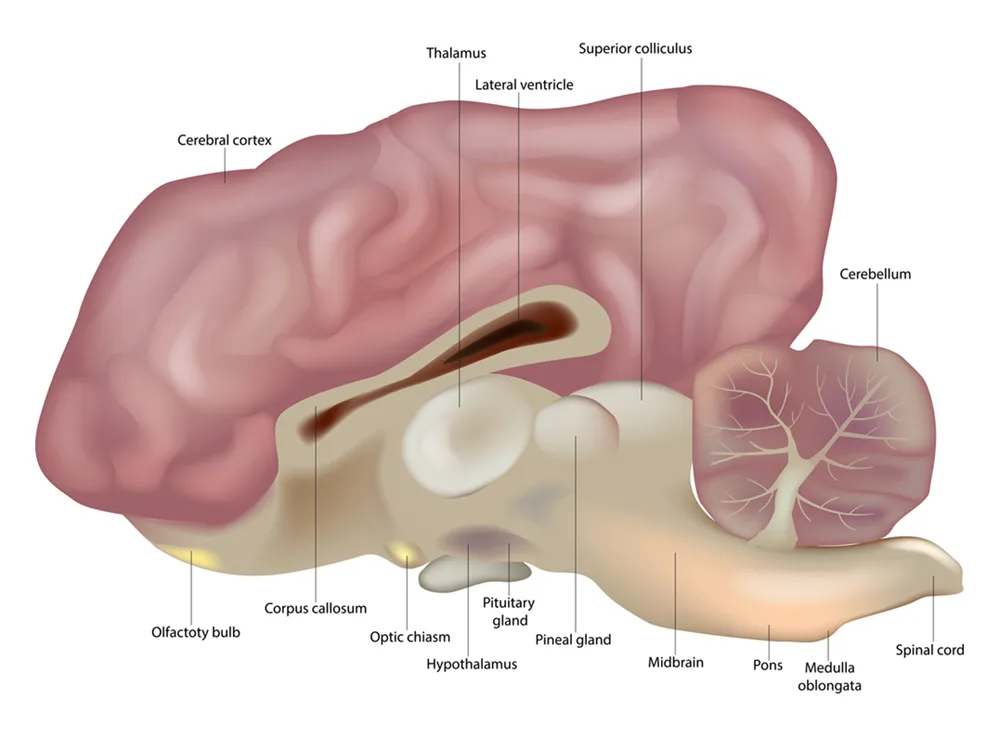

The canine athlete’s brain

How stress, routine, and training impact cognition and performance

When we talk about canine athletes, whether agility dogs, working gundogs, flyball stars, or protection sport competitors, we tend to focus on muscles, joints, diet, and cardiovascular health. Yet, just like in human sport, the brain plays a central role in performance. From learning and memory to stress resilience and focus, the canine brain is constantly shaping how our dogs train, compete, and recover.

THE STRESS FACTOR

Stress is not inherently negative. In fact, moderate, short-term stress can sharpen a dog’s focus and readiness; this is the equivalent of a human athlete’s adrenaline spike before a big event. This is state is called eustress, and it primes the brain to perform. However, chronic stress results in a different picture entirely. Firstly, elevated cortisol levels over time can impair memory and learning, making it harder for dogs to retain new skills. In addition, prolonged stress reduces the brain’s neuroplasticity and its ability to adapt and form new connections. Behaviourally chronic stress may show up as reactivity, poor impulse control, or shutdown behaviours during training or competition.

In sports settings, stress often comes from unpredictability: inconsistent routines, unclear cues from the handler, or overwhelming environments. Dogs that repeatedly experience this may burn out, just as human athletes do.

THE ROLE OF ROUTINE

Routine is more than convenience; it is a neurological anchor. Predictable schedules help regulate a dog’s circadian rhythms, hormone release, and cognitive expectations. Studies in both humans and animals show that regular sleep, feeding, and activity times reduce baseline stress and improve learning efficiency.

For the canine athlete, this means:

- Consistent pre-training rituals help the brain recognise it’s ‘time to work.’

- Regular sleep–wake cycles consolidate memory, which is crucial after learning new skills.

- Predictable recovery days prevent overtraining syndrome, which can affect the brain as much as the body.

Routine also gives the handler an advantage: it reduces decision fatigue for the dog, allowing more brainpower to go into performance tasks rather than constantly interpreting shifting circumstances.

TRAINING AND NEUROPLASTICITY

Training is where the brain truly shines. Every repetition of a jump sequence, weave pole, or obedience exercise strengthens neural circuits. The brain’s capacity to adapt to experience in this way, is true neuroplasticity in action.

High-quality training does more than teach skills:

- Shaping and reward-based training activate the brain’s reward pathways, releasing dopamine. This not only enhances learning but builds a positive emotional state tied to training.

- Variable reinforcement keeps dogs motivated and cognitively flexible.

- Cross-training (e.g., scentwork alongside agility) stimulates different brain regions, improving problem-solving and reducing monotony.

Conversely, harsh methods or over-repetition without reward can lead to neural inhibition, where the brain ‘shuts down’ pathways associated with learning. That’s why positive, varied, and carefully dosed training is so important for long-term cognitive health.

THE EMOTIONAL BRAIN

The canine limbic system, the brain’s emotional centre, is closely linked to performance. Confidence, enthusiasm, and resilience are not just personality traits; they are neurobiological states shaped by early life, training experiences, and environment.

- Dogs trained with positive reinforcement show more optimism in cognitive bias studies, indicating healthier emotional processing.

- Fear or punishment-based systems can create long-term changes in the amygdala, leading to anxiety and reduced performance under pressure.

This means protecting the emotional brain is just as critical as conditioning the body.

PRACTICAL TAKEAWAYS

- Manage stress wisely: Accept small doses as performance fuel, but guard against chronic stress by providing downtime, safe spaces, and stress-relieving outlets (like sniffing or off-leash walks).

- Build predictable routines: Stick to regular feeding, training, and resting cycles. Small rituals, like a consistent warm-up, help anchor the brain.

- Train for the brain, not just the body: Keep sessions short, positive, and varied. Celebrate problem-solving as much as physical achievement.

- Prioritise recovery: Mental fatigue is real. Give the brain as much time to recover as the muscles.

- Protect the emotional core: Nurture confidence, reward effort, and ensure your dog’s sense of safety is never compromised.

FINAL THOUGHTS

The canine athlete’s brain is not just a control centre for the body; it is a living, adapting organ that shapes how dogs perceive, learn, and perform. By understanding how stress, routine, and training sculpt cognition, we not only improve results in terms of performance but also protect the long-term well-being of the animals we love.

The rise of

tick-borne diseases

What’s happening in South Africa

Tick-borne diseases are an increasing concern for dog owners across South Africa. Once thought of as a ‘seasonal’ problem, ticks and the illnesses they carry are now being seen throughout the year. With climate shifts changing tick activity and survival, and with more cases being reported by vets, it’s more important than ever for owners to understand the risks and take proactive steps to protect their dogs.

WHAT’S HAPPENING RIGHT NOW

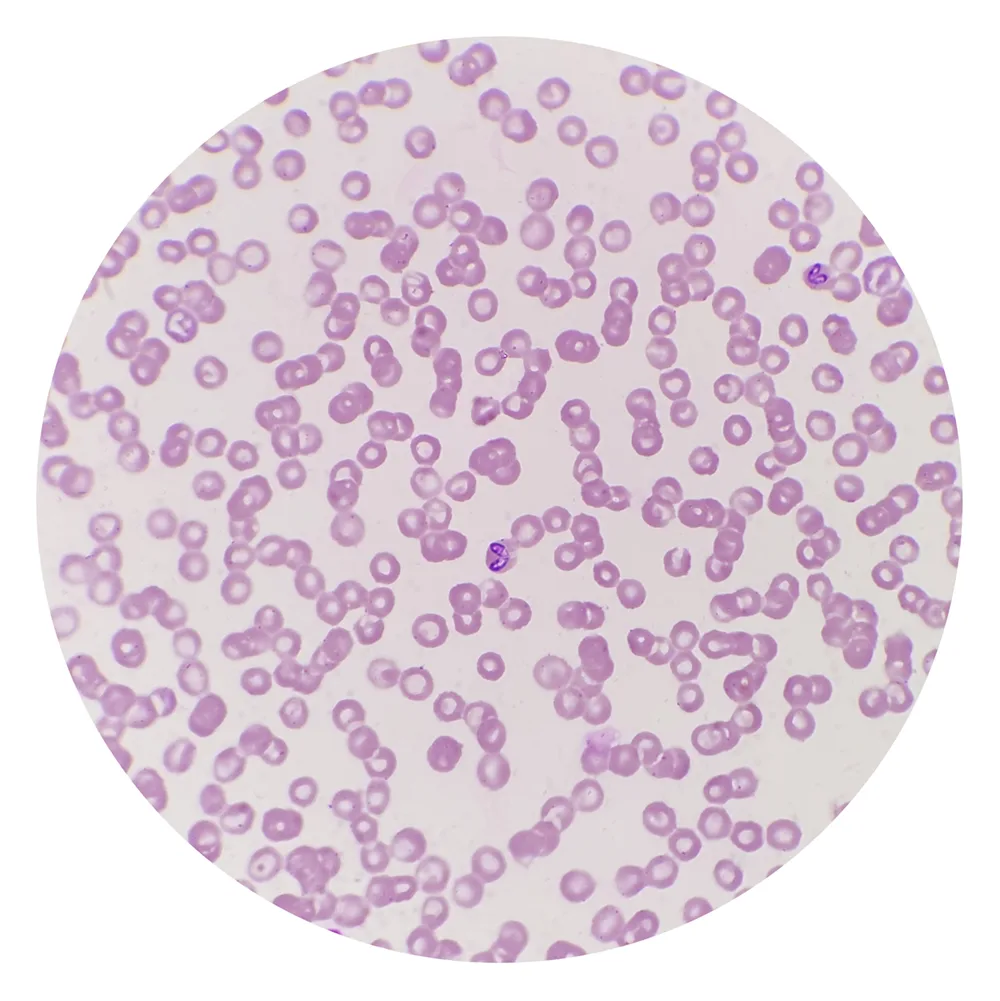

South African vets are reporting a noticeable increase in cases of ehrlichiosis (commonly known as ‘tick-bite fever’) and babesiosis (‘biliary’). These diseases are transmitted when infected ticks bite and feed on a dog’s blood.

- Ehrlichiosis is caused by a bacterium (Ehrlichia canis) and often results in fever, lethargy, swollen lymph nodes, loss of appetite, and, in chronic cases, bleeding disorders and bone marrow suppression.

- Babesiosis is caused by protozoan parasites that invade red blood cells, leading to anaemia, jaundice, weakness, and in severe cases, organ failure.

Both can be fatal if not treated promptly, and sadly, many cases are advanced by the time dogs reach the vet.

What about Lyme Disease and Anaplasmosis

You may have heard of tick-borne diseases, such as Lyme Disease and Anaplasmosis, in dogs.

- Lyme Disease is caused by the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi and spread by deer ticks (Ixodes species) in North America and Europe. These ticks don’t occur in South Africa, so true Lyme disease does not affect dogs here.

- Anaplasmosis (caused by Anaplasma phagocytophilum or A. platys) has been reported in some African countries and occasionally in South Africa, but it remains far less common than ehrlichiosis and babesiosis.

For South African owners, then, the main threats remain ehrlichiosis (tick-bite fever) and babesiosis (biliary), and these are the diseases you need to be most vigilant about.

HOW CLIMATE AFFECTS TICK CYCLES

Traditionally, South African dog owners expected ticks to be a problem mainly in the warmer, wetter months. But recent changes in climate - particularly warmer winters and shifts in rainfall - have extended tick survival and reproduction periods.

- Longer summers and milder winters mean ticks can remain active year-round, rather than dying off or going dormant.

- Increased humidity creates ideal conditions for tick larvae and nymphs to thrive in grass and bush.

This means the old assumption that ‘winter is safe’ no longer holds true. Dogs may now be at risk of tick-borne diseases at any time of year.

OTHER FACTORS THAT CONTRIBUTE

Beyond climate change, other factors also play a role in the increase. These include:

- Changing wildlife and livestock movements as a consequence of land-use changes also bring ticks into closer contact with suburban and peri-urban areas.

- The increasing pet population and the interconnectedness between wild and domestic animals via shared tick species facilitate the spread of pathogens.

- A lack of financial resources for tick control and vaccines in some areas, coupled with insufficient data on disease distribution, hinders effective management.

WHY THE RISE MATTERS

Beyond the immediate health risks to pets, the increase in tick-borne disease has broader implications:

- Treatment costs can be significant, especially in complicated or advanced cases requiring hospitalisation.

- Drug resistance is becoming a concern, as parasites adapt to commonly used treatments.

- Zoonotic spread is a concern, while as most tick-borne diseases in dogs do not directly infect humans, the ticks themselves can transmit other pathogens to people, making tick control an essential public health measure as well.

PREVENTION STRATEGIES

The good news is that with vigilance, owners can significantly reduce their dogs’ risk of tick-borne disease.

- Tick control products: Regular use of veterinary-recommended spot-ons, collars, or oral tick preventatives is the single most effective strategy.

- Check your dog daily: Run your hands over your dog after walks, especially around the ears, neck, belly, and between toes. Promptly remove any ticks with a proper tick remover.

- Manage the environment: Keep grass short, clear leaf litter, and limit access to areas known for heavy tick infestations.

- Routine vet checks: If your dog lives in a high-risk area, regular blood tests may help detect early infections.

- Know the signs: Lethargy, fever, pale gums, loss of appetite, or sudden weakness should always be treated as red flags - early veterinary intervention can save lives.

Tick hot spots on your dog’s body

When checking your dog, pay special attention to these areas:

- Around the ears and inside the ear folds.

- Under the collar and around the neck.

- Between the toes and under the paw pads.

- Along the belly and groin area.

- Around the tail base and under the tail.

- In the armpits, where the legs meet the body.

FINAL THOUGHTS

Tick-borne diseases are no longer just a seasonal worry in South Africa; they’re an everyday reality. As climate change alters tick cycles and disease patterns, owners must remain proactive year-round. The best defence is consistent prevention, quick recognition of symptoms, and strong partnerships with veterinarians.

When it comes to feeding our dogs, ‘protein’ is one of the first words most owners look for on a label. We know protein is essential for muscle, energy, skin, and coat, so the higher the percentage, the better… right? Not necessarily. What really matters is not just how much protein a diet contains, but where that protein comes from and how easily your dog can use it.

THE ROLE OF PROTEIN IN DOGS

Protein is made up of amino acids. Dogs need these amino acids to build and repair muscle, produce enzymes and hormones, support the immune system, and keep skin and coat in good condition.

While dogs can make some amino acids themselves, others, called essential amino acids, must come from food. This is where protein quality comes in. A food can be high in crude protein, but if it doesn’t provide the right essential amino acids in usable form, your dog won’t thrive.

QUANTITY: THE CRUDE PROTEIN NUMBER

Pet food labels usually list ‘crude protein %’ as part of the guaranteed analysis. This tells you how much protein is present by weight, but not how digestible it is or how balanced the amino acid profile is.

A food with a protein percentage of 30% might sound great, but if that protein comes mainly from sources dogs can’t digest well, your dog won’t actually benefit from it.

QUANTITY: WHAT REALLY COUNTS

Protein quality refers to:

Digestibility, i.e. how well a dog can break down and absorb the protein.

Amino acid profile, i.e. whether it contains all the essential amino acids in the right balance.

High-quality proteins (like chicken, fish, egg, and certain meats) are highly digestible and provide all essential amino acids. Lower-quality proteins (like some plant proteins, meat by-products, or fillers) may not be as digestible and may lack certain amino acids.

This is why eggs, for example, are considered a ‘gold standard’ protein; they’re almost completely digestible and balanced in amino acids.

THE RISKS OF FOCUSING ON QUANTITY ALONE

Feeding diets based only on high protein percentages can backfire:

- Excess protein that isn’t used is broken down and excreted, which puts unnecessary strain on the kidneys and liver.

- Low-quality proteins can cause digestive upset and produce more waste in the form of poorly formed stools.

- Unbalanced diets may lead to deficiencies in key amino acids, even if the crude protein number looks high.

WHAT TO LOOK FOR IN YOUR DOG'S FOOD

When assessing protein in your dog’s diet, look beyond the percentage on the label. Ask:

- Where does the protein come from? (Named meat or fish sources are best.)

Is there a variety of protein sources to balance amino acid profiles?

Are there unnecessary fillers that boost crude protein without offering real nutritional value?

Is the diet appropriate for your dog’s age, size, and activity level?

FINAL THOUGHT

Protein is vital for every aspect of your dog’s health, but it’s a case of quality over quantity. A diet with moderate but highly digestible, well-balanced protein is far better than one that boasts a high crude protein number from poor-quality sources. When choosing food for your dog, remember: it’s not just the numbers that count, it’s the nutrition behind them.

For too long, dog culture has celebrated the confident extrovert: the tail-wagging social butterfly who greets strangers with enthusiasm, bounds into the dog park, and thrives in busy environments. But just like people, not all dogs are wired this way. Some are naturally cautious, sensitive, or reserved. These ‘shy’ dogs are often misunderstood, labelled as ‘problematic,’ or placed into endless training programmes to ‘fix’ their personalities.

The truth is: shyness is not a flaw. It’s simply a temperament. And learning to celebrate introverted dogs, rather than forcing them into roles that don’t fit, may be the next great shift in canine welfare.

TEMPERAMENT, NOT TRAUMA

It’s easy to assume a shy dog must have been neglected, abused, or poorly socialised. While early experiences certainly play a role, many shy dogs are simply born with a quieter, more cautious temperament, just like more introverted humans. Research into canine behaviour shows that genetic influences on personality traits, such as sociability and fearfulness, are significant, meaning that a dog may just be ‘shy’ by nature, without any environmental influence.

Just as we wouldn’t expect every child to be outgoing, we shouldn’t expect every dog to crave constant social interaction.

THE PROBLEM WITH ‘FIXING’ SHYNESS

Traditional approaches often treat shyness as something broken. Owners are encouraged to flood shy dogs with social experiences or push them into overwhelming environments in the hope they’ll ‘come out of their shell.’ While some dogs do gain confidence with careful exposure, others become more stressed, anxious, or withdrawn.

The danger is twofold:

- For the dog: Repeated stress can elevate cortisol and reduce trust in their human.

- For the owner: Frustration builds when the dog doesn’t transform into the expected ‘friendly pet.’

This cycle can erode the human-dog bond, when what shy dogs most need is empathy, patience, and acceptance.

REFRAMING SHYNESS AS STRENGTH

Shy dogs bring unique qualities worth celebrating:

- Loyalty: Once bonded, introverted dogs are often deeply connected to their humans.

- Calm presence: They are less likely to overwhelm guests or charge into chaotic situations.

- Sensitivity: Many shy dogs are highly attuned to subtle cues and thrive in quieter, structured environments.

- Resilience with the right support: Given safe spaces and gentle handling, shy dogs can flourish - not as extroverts, but as confident versions of themselves.

Recognising these traits allows us to value them for who they are, not who we think they ‘should’ be.

SUPPORTING THE SHY DOG

Instead of trying to erase shyness, we can help these dogs live happy, enriched lives by adapting our expectations and environments. Practical steps include:

- Respect their boundaries: Don’t force greetings or interactions, rather let them choose when and how to engage.

- Create safe spaces: Provide quiet retreats at home and during travel so they can decompress.

- Use positive reinforcement: Reward small steps of confidence, but never punish avoidance.

- Educate others: Politely let visitors know your dog doesn’t enjoy being petted or crowded.

- Enrich on their terms: Focus on activities they enjoy, like scentwork, gentle walks, or training games at home.

A CULTURAL SHIFT IN PROGRESS

The ‘shy dog revolution’ is about more than individual owners. It’s about changing the wider culture around dogs. Just as we’ve come to question outdated dominance-based training, we can now question why extroversion is treated as the gold standard.

Rescue organisations, trainers, and breeders all have roles to play: by highlighting the strengths of quieter dogs, adopting language that doesn’t stigmatise shyness, and matching these dogs to homes where they will be cherished rather than ‘fixed.’

FINAL THOUGHTS

Shy dogs are not broken, and they don’t need to be transformed into something they are not. They need understanding, respect, and the freedom to be themselves. By celebrating introverted personalities, we not only improve the lives of these dogs but also expand our own definition of what it means to have a truly rewarding partnership with our best friend.

References

Persson, M. E., Roth, L. S., Johnsson, M., Wright, D., & Jensen, P. (2015). Human-directed social behaviour in dogs shows significant heritability. Genes, Brain and Behavior, 14(4), 337–344. • Haverbeke, A., Laporte, B., Depiereux, E., Giffroy, J. M., & Diederich, C. (2008). Training methods of military dog handlers and their effects on the team’s performances. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 113(1-3), 110–122. • Rooney, N. J., & Cowan, S. (2011). Training methods and owner–dog interactions: Links with dog behaviour and learning ability. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 132(3–4), 169–177. • Overall, K. (2013). Manual of Clinical Behavioral Medicine for Dogs and Cats. Elsevier.

Fostering puppies

Georgia’s journey with Woodrock Animal Shelter

Every year, animal shelters across South Africa are overwhelmed by puppies in need of urgent care. Foster homes are the lifeline that make survival possible, especially for tiny puppies who require round-the-clock feeding, warmth, and vigilant care. At Woodrock Animal Shelter, dedicated volunteers open their homes and hearts to give these little ones a chance. We spoke to Georgia Harley, a fosterer who is currently caring for some of Woodrock’s younger arrivals, to find out what the experience is really like.

GETTING STARTED

DQ: How did you first get involved with fostering puppies for Woodrock?

Georgia: I began fostering in 2023, shortly after leaving my full-time job. I’d lost my own puppy, Kimchi, earlier that year, and because he came to me in a ‘sort of’ foster situation, I wanted to honour his memory. Fostering felt like the right way to fill some of my time - and honestly, who doesn’t love a puppy?

What helps me is remembering the bigger picture:

letting these ones go makes space to help more.

– Georgia Harley

DQ: What motivated you to start fostering, and what keeps you going?

Georgia: Rescue organisations like Woodrock always need fosterers. I’ve taken breaks when life got busy, but fostering found me again this year when I came across people selling puppies on the side of the road. Woodrock didn’t have anyone who could take the pups that night so I stepped in and just kept going! I’m lucky to have a family friend, Manuela, who shares the responsibility - if I’m tied up with work, she takes over for a bit.

WHAT IT INVOLVES

DQ: What does a typical day look like with very young foster puppies?

Georgia: The youngest I’ve cared for were just three weeks old and still on bottles. At that stage, they feed every five hours or so. Settling them in can take a little time, whether they have come directly from their mother or from another foster home, but once they find their rhythm, the day starts early, usually around 5am. Feed, clean, cuddle, sleep, repeat. As they grow, there’s more playtime, less sleep, and a gradual shift to solid food. I usually give a last bottle around midnight, moving it earlier as they get older.

DQ: What are the biggest challenges in those early weeks?

Georgia: I’m not as experienced as lots of the other fosterers at Woodrock, but I suppose I would say that bottle-feeding can be tough at first, whether they’ve come from their mother or another foster home. The pups just need to get used to you and your way of feeding and that can take a bit of time. And sadly, very young pups are vulnerable to health problems. My current two are runts from a large litter, so getting them stable has been stressful at times. Right now, our main hurdle is transitioning from the bottle to solids; it’s always a process, but these two are finding it particularly tricky.

DQ: How do you handle veterinary care, like vaccinations and deworming?

Georgia: Because I live outside Gauteng and close to Woodrock, I take my pups directly there for their vaccines once they’re old enough. Until then, hygiene is everything - no exposure to unknown dogs, limited handling, no outings. Woodrock’s medical team is always on hand, and deworming is scheduled regularly. They supply the medication, and I just follow the cycle.

In terms of veterinary care, if I have any concerns, I just contact Sarah, the foster coordinator, and she tells me what to do or if I need to take them somewhere and when I need to do that.

DQ: What signs tell you a puppy might not be thriving?

Georgia: Eating is the biggest one. At this age, eating and sleeping is their whole job. If they’re not feeding well, or if their weight isn’t going up, that’s a red flag. I also watch their energy - even though they sleep a lot, a pup that seems unusually flat needs attention. My rule of thumb is to trust my gut. If something feels off, I reach out to the Woodrock team straight away. As I said, I’m not as experienced as lots of the other fosterers at Woodrock who have been doing it for years, so if something worries me, I immediately ask for help.

DQ: Do you have any tips for keeping puppies healthy in those first weeks?

Georgia: Document everything. I write down when and how much they eat, and any changes I notice. If a puppy who normally drinks 70ml suddenly only takes 20ml, I know immediately something’s wrong. It also helps if you need to give a detailed history to the vet later on.

Do it. Even if you don’t have experience, the Woodrock team will

support you every step of the way.

– Georgia Harley

EMOTIONAL SIDE

DQ: How do you cope with saying goodbye when they’re adopted?

Georgia: It definitely gets easier with time and more practice. My first litter turned into a ‘foster fail’ - I kept Kay. Since then, I’ve had others I would have loved to keep, but you can’t keep them all. What helps is remembering the bigger picture: letting them go makes space to help more. And seeing the joy of the adopters is so rewarding - you know the pups are going to loving homes.

DQ: Do you ever hear from the new families?

Georgia: Yes, I’m lucky to get updates from quite a few of them, even years later. Woodrock also passes on photos when adopters share them. It’s wonderful to see how the puppies grow into their new lives. Of course, it’s a personal choice on the part of the adopters – if they don’t want to stay in touch you have to respect that but as a fosterer, it is really nice to hear how the pups are doing!

ADVICE FOR NEW FOSTERERS

DQ: What would you say to someone considering fostering for the first time?

Georgia: Do it. If you’re unsure about bottle babies, you can always start with older pups or adult dogs. You’ll have full support from the Woodrock team and learn as you go. They’ll match you with the right dog for your experience level and over time it will get easier and easier.

DQ: What support does Woodrock provide?

Georgia: Everything you need. Sarah, the foster coordinator, is just a call away 24/7, and there’s a community of fosterers who share advice and encouragement (and love receiving cute puppy videos!). Financially, Woodrock covers food and all medical costs, so it doesn’t need to cost you anything, though if you choose to buy supplies yourself, it’s always appreciated. Your role is to be the caregiver, and you’ll get everything you need to do that and better yet, you’ll never feel alone in it!

DQ: What’s the most rewarding part for you?

Georgia: Watching the puppies grow and hit milestones - from learning to play to interacting with each other - is amazing. But the best part is meeting the excited adopters and knowing that they’re about to become someone’s much-loved family member.

CLOSING THOUGHTS

Fostering is one of the most powerful ways to change the course of a dog’s life. Volunteers like Georgia - and the wider Woodrock fostering community – give puppies not just survival, but the chance to thrive. For anyone considering fostering, her message is simple: don’t hesitate.

Find a KUSA-accredited club or instructor near you at www.kusa.co.za, or search local Facebook groups for agility enthusiasts in your region.

The new

wave of

tech for

dogs

GPS trackers, activity monitors, AI feeders:

gimmick or game-changer?

Technology has transformed almost every part of our lives, and now it’s making its way into how we care for our dogs. From GPS collars that track every step, to wearable monitors that measure sleep and heart rate, to AI-powered feeders that promise the perfect meal schedule, the pet tech industry is booming. But are these gadgets truly improving the way we understand and care for our dogs, or are they just another wave of expensive gimmicks?

GPS TRACKERS: SAFETY NETS OR SURVEILLANCE TOOLS?

GPS collars and tags have grown in popularity, especially among owners of escape-prone breeds or rural dogs with plenty of space to roam. These devices can:

- Pinpoint a dog’s location in real time.

- Track exercise and walking routes.

- Offer ‘safe zone’ alerts if a dog leaves a designated area.

For worried owners, this tech undoubtedly provides some peace of mind and the ability to locate a missing dog quickly can be life-saving. However, some trackers rely on cellular coverage, which can be patchy in rural South Africa, and battery life often limits their usefulness.

Verdict: A game-changer for safety in the right contexts, but only if you manage expectations around coverage and battery life.

ACTIVITY MONITORS: FITNESS TRACKERS FOR DOGS

Activity monitors measure steps, rest, sleep quality, and sometimes even heart rate or calories burned. For canine athletes or overweight pets on weight-loss programmes, these devices can provide valuable data. Research has shown that objective monitoring helps owners stick to exercise routines, and can even pick up subtle changes in rest or movement that may signal illness before it’s visible.

The downside? Not all data is accurate. Step counts can vary wildly between devices, and interpreting ‘sleep quality’ in dogs is more complicated than in humans. These tools are best viewed as trend-trackers rather than precise medical instruments.

Verdict: Useful for motivated owners and professionals, but not a replacement for human observation and veterinary insight.

AI-POWERED FEEDERS: CONVENIENCE OR OVERKILL?

Automated feeders are nothing new, but the latest generation goes further. They use AI to:

Portion food according to the dog’s weight, breed, and age.

Track feeding times and adjust schedules.

Link to apps that monitor how quickly your dog eats.

For busy households, these devices can reduce the risk of missed meals or inconsistent feeding. Some also claim to help prevent obesity by keeping portions precise. Yet, concerns remain. Feeding is more than nutrition; it’s part of bonding. Outsourcing it entirely to a machine risks losing that daily moment of connection. And, of course, no feeder can assess whether a dog is thriving on a particular diet; that still requires human observation and veterinary guidance.

Verdict: A convenience tool that may suit some lifestyles but not a substitute for mindful feeding and interaction.

ARE THESE TOOLS GIMMICKS OR GAME-CHANGERS?

The truth lies somewhere in between. For some owners, tech devices bring real improvements in safety, health management, and daily routines. For others, they may become abandoned gadgets once the novelty wears off.

The key is context:

- For working or sport dogs, trackers and monitors can provide meaningful insights into fitness and recovery.

- For nervous owners, GPS collars can bring peace of mind.

- For busy households, AI feeders might help keep dogs on a steady routine.

But no piece of technology replaces observation, hands-on care, and the deep human-canine bond built through time, presence, and attention.

Practical tips for choosing dog tech

- Start with a need, not a product. Don’t buy a device just because it exists; identify whether it solves a real problem for you and your dog.

- Check the data. Look for independent reviews or studies on accuracy, not just company marketing.

- Consider lifestyle. For instance, GPS trackers that require daily charging may frustrate busy owners.

- Don’t ignore the basics. Tech should complement, not replace, vet care, training, and enrichment.

FINAL THOUGHTS

Pet tech is not inherently good or bad. For some, it will genuinely improve canine welfare and owner peace of mind. For others, it’s a shiny distraction. The challenge is to use technology thoughtfully: as a tool to support health and safety, without forgetting that no app or AI can replace the joy of hands-on time with your dog.

YOUR DOG QUESTIONS ANSWERED

How can I help my puppy to be smarter around cars? We live on a property where cars come in and out during the day. I'm normally there with him but I'm nervous about him if I'm not around.

Your concern is spot on, as cars are one of the biggest dangers for young dogs, and it’s important to teach safe habits early. Puppies don’t naturally understand that vehicles can hurt them, so you’ll need to put management and training in place together.

1. Management comes first

Until your puppy has reliable training, don’t rely on him to make safe choices around cars. Use physical barriers such as a fenced garden, playpen, or long line to keep him from running near vehicles unsupervised. If you’re not around, the best way to keep him safe is to keep him indoors. Management is the most important layer of safety.

2. Teach strong recall and boundary cues

Start recall training away from cars, using positive reinforcement so that coming when called becomes second nature. You can also introduce a ‘wait’ or ‘stay back’ cue at the edge of the driveway, rewarding him for holding back while you walk closer to the car. Practice daily in short, calm sessions.

3. Desensitise to car movement

Puppies may chase or dart toward moving vehicles. Have someone slowly drive in and out while you keep your pup on a leash at a safe distance. Reward calm behaviour (sitting, watching you, not lunging). Over time, this builds the habit of staying settled rather than reacting to cars.

4. Encourage focus on you, not the car

Play training games near parked cars, rewarding eye contact and engagement with you. This teaches your puppy that the best rewards come from you, not from investigating the vehicle.

5. Never assume ‘he knows’

Even as he grows up, keep safety measures in place. Many accidents happen when owners believe their dog is road-smart. Continue to supervise, manage the environment, and reinforce boundaries.

Final thoughts

Your puppy won’t automatically learn to be ‘car smart’; he’ll learn through a combination of training, consistency, and careful management. Barriers, supervision, and strong recall cues are your best tools. Over time, he’ll develop safer habits, but accidents can always happen, and the best way to keep him safe is just to keep him away from cars as much as possible.

Lots of people say it isn't a good idea to have two siblings from the same litter. Why is that?

Bringing home two puppies from the same litter can sound like a dream. It’s easy to assume that the two together will be built-in company for each other, thrive as playmates and enjoy growing up together. But there are good reasons why many trainers and behaviourists advise against it:

1. ‘Littermate synedrom’

When two puppies are raised together, they often form an unusually intense bond with each other. This can make them less interested in people, slower to develop independence, and more prone to separation anxiety if they’re apart. It doesn’t happen in every case, but it’s common enough that it’s become known as littermate syndrome.

2. Training challenges

Two puppies at once means double the house-training, double the chewing, and double the supervision. Because they’re so focused on each other, they may be harder to engage in training sessions, making it difficult for each to learn boundaries, social skills, and obedience.

3. Behavioural risks

Siblings can squabble more fiercely as they mature, especially once they hit adolescence. What starts as playful wrestling can sometimes turn into real fights, which can be stressful (and even dangerous) for the dogs and their owners.

4. Owner burnout

Caring for one puppy is already a huge time and energy commitment. Two can quickly become overwhelming, and unfortunately this sometimes leads to one (or both) being rehomed.

That said, it’s not impossible, to raise two puppies from the same litter together. Experienced owners can raise siblings successfully, but it requires a lot of extra work, including training and socialising the pups separately, giving them one-on-one time, and sometimes even walking them apart in the beginning.

For most families, it’s usually a better idea to bring one puppy home first, focus on their development, and then consider adding another dog later.

Tips for if you already have littermates

- Train separately: Take each puppy out alone for short sessions so they learn to focus on you.

- One-on-one time: Spend individual time with each pup.

- Separate socialisation: Expose them to new people, places, and experiences without their sibling there.

- Sleep apart sometimes: Gradually get them used to being in different crates or beds so they learn independence.

- Watch for tension: As they mature, keep an eye out for escalating sibling rivalry and intervene early with professional help if needed.

Products we love

Shopping fun

PaleoPet Pure 100% Green Beef Tripe for Dogs

Humans may find tripe to be somewhat of an acquired taste (and smell), but dogs absolutely love it! Our tripe has been thoroughly washed and cleaned for you, while retaining all the nutrition of unbleached tripe. It’s easy to serve and store and has so many health benefits for adult and senior dogs especially.

Tripe is rich in trace minerals, while moderate in protein and fat. It is a great complementary raw food addition to a diet for dogs who may struggle with constipation or need foods that are easier to digest. Tripe doesn’t contain any bone, but still maintains a perfect calcium phosphorus balance, which is rare for animal protein without bone content.

Tripe can be used as a basis for a ketogenic diet for dogs with cancer or epilepsy where one should feed low to no carbohydrate, moderate protein, and high fat. Tripe can also entice dogs who may not feel all that well and are reticent to eat.

Our 100% Green Beef Tripe (and nothing else) is made from the best quality local beef with no preservatives, colourants, or artificial flavourants.

The PaleoPet Pure range is FSA Food Safety certified and DALRRD registered. Also available in convenient, pre-frozen 1.5 Kg and 750g tubs or as a box of 12 individually wrapped 100g Patties. The tubs are re-usable, recyclable, and PBA-free.

Products can be purchased online at www.paleopetpure.com and delivered to your door or bought at selected retailers.

follow us on Instagram @dogquarterlymag and Facebook dqmagazine

stay tuned for the next issue of